Alphabet Project, Part 5

Previous entries in this series:

Step 4 - adding (more) musicality

Without veering too deeply into extended vocal technique, there are three components for each note we can vary to create a more musically interesting piece from our first draft:

- dynamic

- pitch

- phoneme sound/quality

Dynamics

Dynamic is perhaps the simplest parameter here. In my head, the more frequent a part’s pulse is, the more it should blend, dynamically, with the whole piece. This means that for parts with the lowest sound event frequencies, their sounding notes will sound more as interruptions, while the rest of the parts will provide more of a background constancy.

This is easy enough, in theory, to generate an algorithm for. For each measure, we can

take a look at the fraction of sounding note events / total events map that inversely

to a list of possible dynamics (i.e. smaller fraction = louder sound)

To calculate the density of a measure:

def density({ {n, d}, events}) do

# `Enum.count/2` chains `Enum.filter/2` and `length`

# Here we get the count of sounding note events

Enum.count(events, fn event ->

event == "c8"

end) / n # and divide it by the total number of events

endLooking through a sampling of the generated densities, it’s possible to generate a density -> dynamic mapping.

def to_dynamic(density) do

cond do

density == 0 -> ""

density > 1 -> "\\ppp"

density >= 0.6666 -> "\\pp"

density >= 0.5 -> "\\p"

density >= 0.3333 -> "\\mp"

density >= 0.25 -> "\\mf"

density >= 0.1 -> "\\f"

density >= 0.05 -> "\\ff"

true -> "\\fff"

end

endI set the breakpoints in the cond above based on a very

unscientific analysis of the fractions present in an attempt to skew the

resulting dynamics towards the quiet side. Let’s see how that worked out.

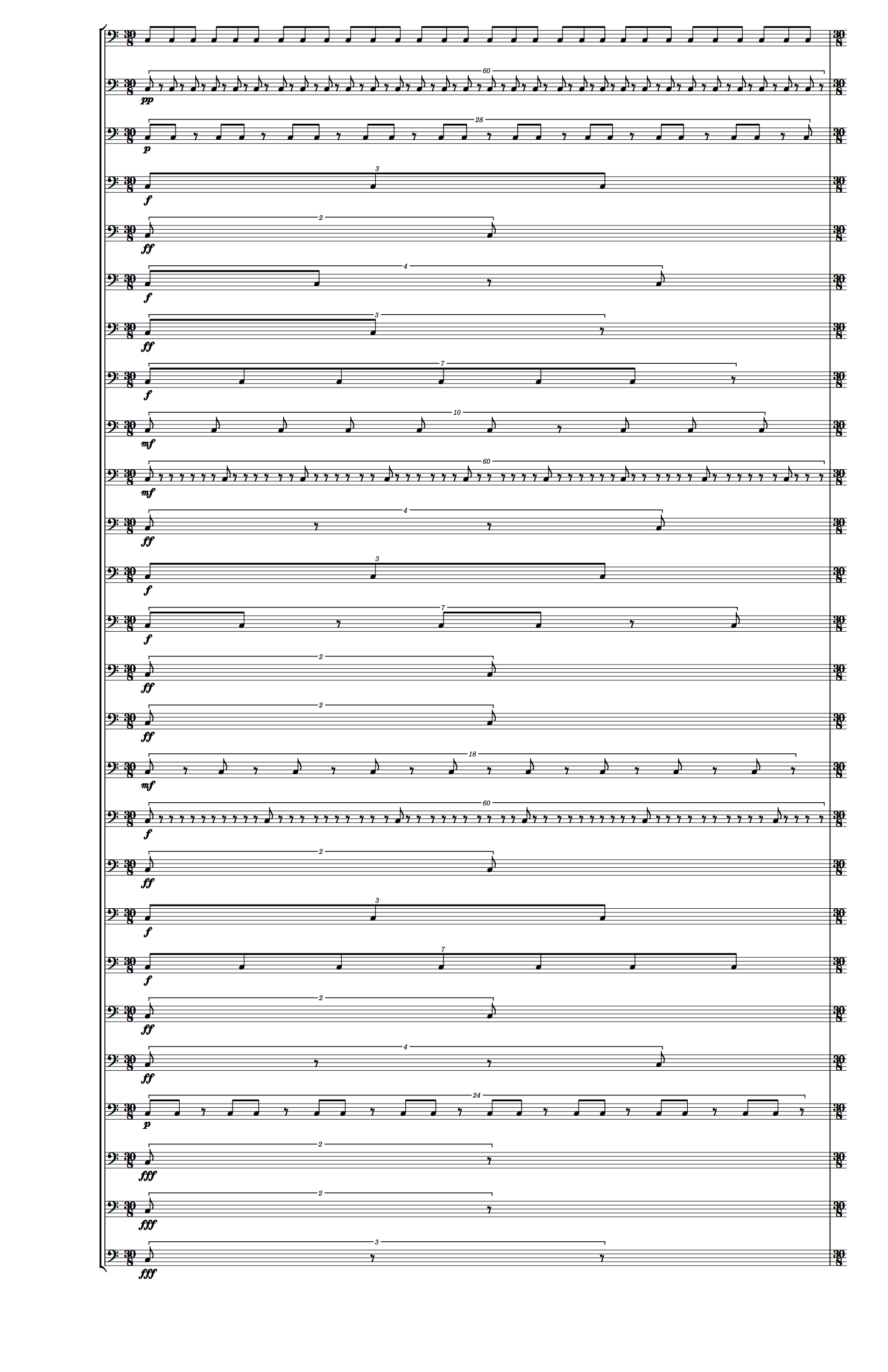

We start off with a lot of forte and louder on the first page, and by the last page we’re mostly in the pianissimo range.

Which is potentially fine, depending on what you want the dynamic envelope of the piece to be. Personally, I’d rather it start

off on the quieter side, and build intensity, perhaps with a bit of a denouement through the last pages. But it’s unlikely

that a single algorithm is going to get me that. Fortunately, there’s an easier way.

Rather than a single density -> dynamic mapping, we can create as many as we want, and pick which one to use based on the current measure. Something like

def to_dynamic(density, measure_index) do

envelope = cond do

measure_index <= 20 -> ["ppp", "ppp", "ppp", "ppp", "pp", "pp", "p", "mp"]

measure_index <= 100 -> ["ppp", "pp", "p", "mp", "mf", "f", "ff", "fff"]

true -> ["ppp", "ppp", "pp", "pp", "mp", "mf", "f", "ff"]

end

_to_dynamic(density, envelope)

end

def _to_dynamic(density, dynamic_envelope) do

with [d1, d2, d3, d4, d5, d6, d7, d8] <- dynamic_envelope do

cond do

density == 0 -> ""

density > 1 -> d1

density >= 0.6666 -> d2

density >= 0.5 -> d3

density >= 0.3333 -> d4

density >= 0.25 -> d5

density >= 0.1 -> d6

density >= 0.05 -> d7

true -> d8

end

end

endand of course this can be tailored to personal aesthetics for the piece. For the next draft, I’m working with this envelope map:

envelope = cond do

measure_index <= 20 -> ["ppp", "ppp", "ppp", "ppp", "ppp", "ppp", "ppp", "ppp"]

measure_index <= 40 -> ["ppp", "ppp", "ppp", "pp", "pp", "pp", "p", "p"]

measure_index <= 60 -> ["ppp", "pp", "pp", "p", "p", "p", "mp", "mp"]

measure_index <= 80 -> ["ppp", "pp", "p", "p", "mp", "mp", "mp", "mf"]

measure_index <= 100 -> ["ppp", "pp", "p", "p", "mp", "mf", "mf", "f"]

measure_index <= 120 -> ["ppp", "pp", "p", "mp", "mp", "mf", "f", "ff"]

measure_index <= 140 -> ["ppp", "pp", "p", "mp", "mf", "f", "ff", "fff"]

measure_index <= 160 -> ["ppp", "pp", "p", "mp", "mf", "f", "f", "ff"]

measure_index <= 180 -> ["ppp", "pp", "p", "mp", "mf", "mf", "f", "f"]

true -> ["ppp", "ppp", "pp", "p", "mp", "mp", "mf", "f"]

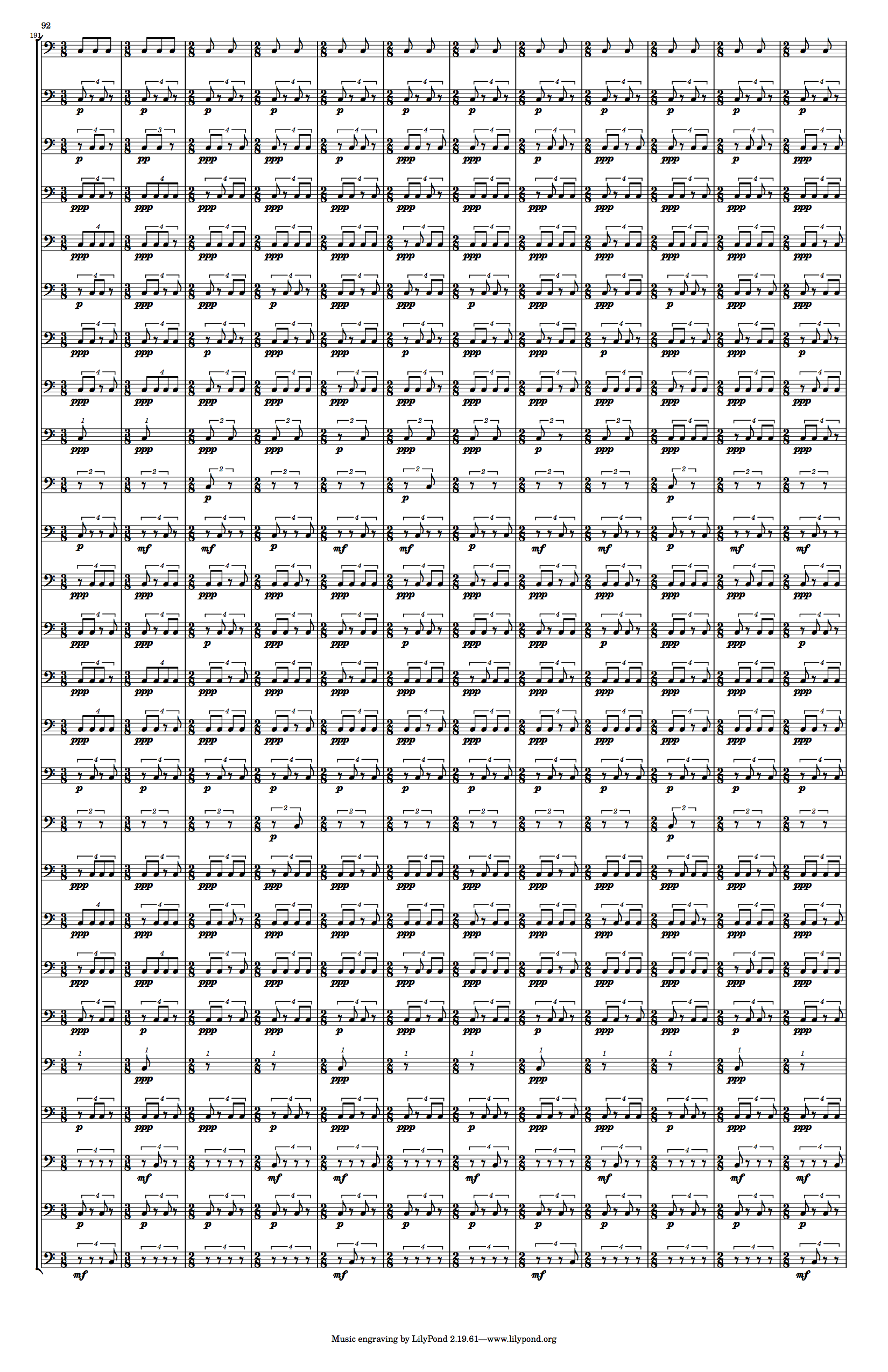

endClearly the first page will be entirely pianississimo, so I won’t bother printing

that out. Let’s take a look at the last page:

That looks like something we can work with! There may be additional tweaking we can do, but to my mind we have the framework to make those tweaks, and that means it’s time to move on to pitch.

Pitch

For pitch, I want the pulse to maintain a single pitch throughout the piece, to anchor

the pulse-iness of it. Let’s say that pitch is C. Then every other part begins on C as well,

and gradually the pitch collection expands by the end of the piece. The question then becomes

how to handle that expansion.

A quarter tone chromatic scale has 24 distinct pitches, so it would be possible to generate

a tone row from those pitches to determine the order of the pitch set expansion.

With the pulse remaining on C throughout, and one line for each of those pitches

(meaning two lines on C for a very slight sense of anchoring), that leaves

one line left to account for.

There are two options here that I like for a first pass:

- a third part stays (or returns) to

C - the part with the lowest event frequency (

zunlesszis the pulse, in which case it would beq) plays the prime form of the quarter tone chromatic row we’ve generated.

Before we get too far down the rabbit hole, let’s generate that pitch row. I decided to use a row built off the harmonic overtone series, with the pitches in order of their first appearance in the series. Or at least approximate first appearance; since most equal tempered pitches don’t ever appear in the overtone series I did some creative rounding to keep things/me sane.

One evening of looking up the first 64 overtones on the internet later, I came up with a working row, based on A

Transposed to begin on C, and using LilyPond accidentals (qs = quarter sharp, tqf = three quarters flat, etc.),

we get

c g eqf btqf d fqs aqf bqf ctqs ef eqs ftqs

atqf a cqs cs etqf e f fs af bf b bqsTaking choice 2 from above, with the z line performing that tone row’s prime form,

we’re left with the 24 other rows to gradually spread to encomass the row.

Here’s the description of the algorithm for how I want to fill out that expansion

every part begins on `c`, the first pitch in the row

until every pitch is accounted for:

find the pitch currently with the most voices still singing it

divide those voices in half, rounding to integers as necessary

half (or the larger number) transition one at a time to the new pitch

the rest remain on their original pitch

In our case, this would start off like this:

[c: 24]

[c: 12, g: 12] # over a series of twelve individual steps

[c: 6, g: 12, eqf: 6]

[c: 6, g: 6, eqf: 6, btqf: 6]

and so on, and eventually each pitch has just a single voice singing itWhile building up list, we also want to create a list of conversion steps. The code for this looks like this:

defmodule PitchGenerator.V2 do

@pitches ~w( c g eqf btqf d fqs aqf bqf ctqs ef eqs ftqs atqf a cqs cs etqf e f fs af bf b bqs )

@number_of_parts 24

def calculate_conversion_steps do

# all voices start on "c"

starting = [{"c", @number_of_parts}]

starting_index = 1

build_steps(starting, starting_index, 0, [])

end

# if we've added every pitch, return the accumulated steps

def build_steps(current, index, step_count, acc) when index == @number_of_parts do

acc

end

# otherwise

def build_steps(current, index, step_count, acc) do

# find the pitch with the highest vox_count, and its index

{ {pitch, vox_count}, max_tuple_index} = Enum.with_index(current) |> Enum.max_by(fn { {_p, v}, _i} -> v end)

# calculate the number of voices to switch to the next pitch, rounding up

next_vox_count = round(vox_count / 2)

new_max_tuple_vox_count = vox_count - next_vox_count

# update the list with the new vox count for the pitch we found at the beginning

next = List.replace_at(current, max_tuple_index, {pitch, new_max_tuple_vox_count})

# and add the next pitch with its next_vox_count

++ [{Enum.at(@pitches, index), next_vox_count}]

# add the correct number of conversion steps to the step accumulator

new_acc = acc ++ generate_conversion_steps(pitch, Enum.at(@pitches, index), next_vox_count)

# recur

build_steps(next, index + 1, step_count + next_vox_count, new_acc)

end

def generate_conversion_steps(from, to, count) do

Stream.cycle([{from, to}]) |> Enum.take(count)

end

endRunning PitchGenerator.V2.calculate_conversion_steps() returns a list of pitch conversion tuples:

[{"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"},

{"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"},

{"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"}, {"c", "eqf"}, {"c", "eqf"}, ...]Once we have our list of pitch shifts, we can build up a pitch-per-measure list for each part. To determine the order of parts that shift pitches, I’m going based on letter frequency order (etaoin…jxqz)

To seed the measures, we create a list of tuples in the form {letter, [ordered pitches for measures]} and iterate through it.

Explanation:

Each part starts with 3 measures of c, since we have 60 conversions

but 202 measures, and we want the switches spaced out evenly by measure length

part_measures = [

{"e", ["c", "c", "c"]}, {"t", ["c", "c", "c"]}, ..., {"q", ["c", "c", "c"]}

]

conversion_steps = [{"c", "g"}, {"c", "g"}, ...]

for each tuple in conversion_steps:

for each set of part measures, in order:

if the last pitch in the measure list is the `from` pitch of the conversion:

append the `to` pitch to the measure list 3 times

(3 times because we have 60 conversions, but 202 measures,

so we want them to be spaced out evenly)

otherwise:

get the last pitch in the measure list and append it 3 times

for each set of part measures:

make sure the length of the measures list is 202 by duplicating the final

item in the pitch list as many times as necessaryActual code:

defmodule PitchGenerator.V2 do

...

def letters_by_frequency(pulse) do

least_frequent = case pulse do

"z" -> "q"

_ -> "z"

end

frequencies() |> Enum.to_list

|> Enum.sort_by(fn {_, f} -> f end, &>=/2)

|> Enum.map(fn {l, _} -> l end)

|> List.delete(pulse) |> List.delete(least_frequent)

end

def starting_pitches(pulse) do

letters_by_frequency(pulse) |> Enum.map(fn l ->

{l, ["c", "c", "c"]}

end)

end

def generate_measure_pitches(pulse) do

starting_pitches(pulse)

|> generate_splits(calculate_conversion_steps())

end

def generate_splits(pitches, []) do

# if the step list is empty, make sure each part has 202 measures

Enum.map(pitches, fn {letter, notes} ->

new_notes = notes ++ (

Stream.cycle([List.last(notes)])

|> Enum.take(202 - length(notes))

)

{letter, new_notes}

end)

end

def generate_splits(pitches, [{from, to}|rest_shifts]) do

# find the first part still playing the pitch we need to shift

{letter_to_shift, _} = Enum.find(pitches, fn {_, notes} ->

List.last(notes) == from

end)

# iterate through

next_pitches = Enum.map(pitches, fn {letter, notes} ->

case letter == letter_to_shift do

# if it's the part to switch, add 3 measures of the next pitch

# 3 measures so space out the conversions evenly (by measure count)

true -> {letter, notes ++ [to, to, to]}

# otherwise, just repeat the current pitch 3 times

false ->

next_pitch = List.last(notes)

{letter, notes ++ [next_pitch, next_pitch, next_pitch]}

end

end)

generate_splits(next_pitches, rest_shifts)

end

...

endOne last piece, and that is the least frequent row, which is iterating through the pitch row we have. In English, this is a simple exercise:

index = 0

for each event in the part:

if it's a rest, leave it

if it's a note, replace the pitch with pitch_row[index]

index++In real code, in part because of the way notes and measures are represented in data, it is rather less simple:

def least_frequent_part_to_lily(letter, pulse) do

part = letter |> @dynamics_generator.measures(pulse)

|> apply_row(0, [])

|> Enum.map(fn { {n, d}, notes} ->

"\\tuplet #{n}/#{d} { #{Enum.join(notes, " ")} }"

end) |> Enum.join("\n")

write_lilypond_file(letter, part)

{:ok, letter}

end

# if we've processed every measure, return the accumulator

def apply_row([], _row_index, acc) do

acc

end

# otherwise, process the next measure

def apply_row([measure|measures], row_index, acc) do

{ {n, d}, notes} = measure

{new_notes, next_index} = apply_row_to_measure(notes, row_index, [])

apply_row(measures, next_index, acc ++ [{ {n, d}, new_notes}])

end

# if we've processed each event in the measure,

# return the processed events and the updated row index

def apply_row_to_measure([], index, acc), do: {acc, index}

# if the analyzed event is a rest, leave it alone

def apply_row_to_measure([n = << "r8", _ :: binary >>|ns], index, acc) do

apply_row_to_measure(ns, index, acc ++ [n])

end

# otherwise, replace the `c` with the next pitch in the row

# and increment the row index

def apply_row_to_measure([n|ns], index, acc) do

apply_row_to_measure(ns, index + 1,

acc ++ [Regex.replace(~r/c/, n, Enum.at(@pitches, rem(index, length(@pitches))))])

endWith all these pieces, we can generate a new version of the score, including our rhythmic, dynamic, and pitch modifications. Let’s see what we’ve got.

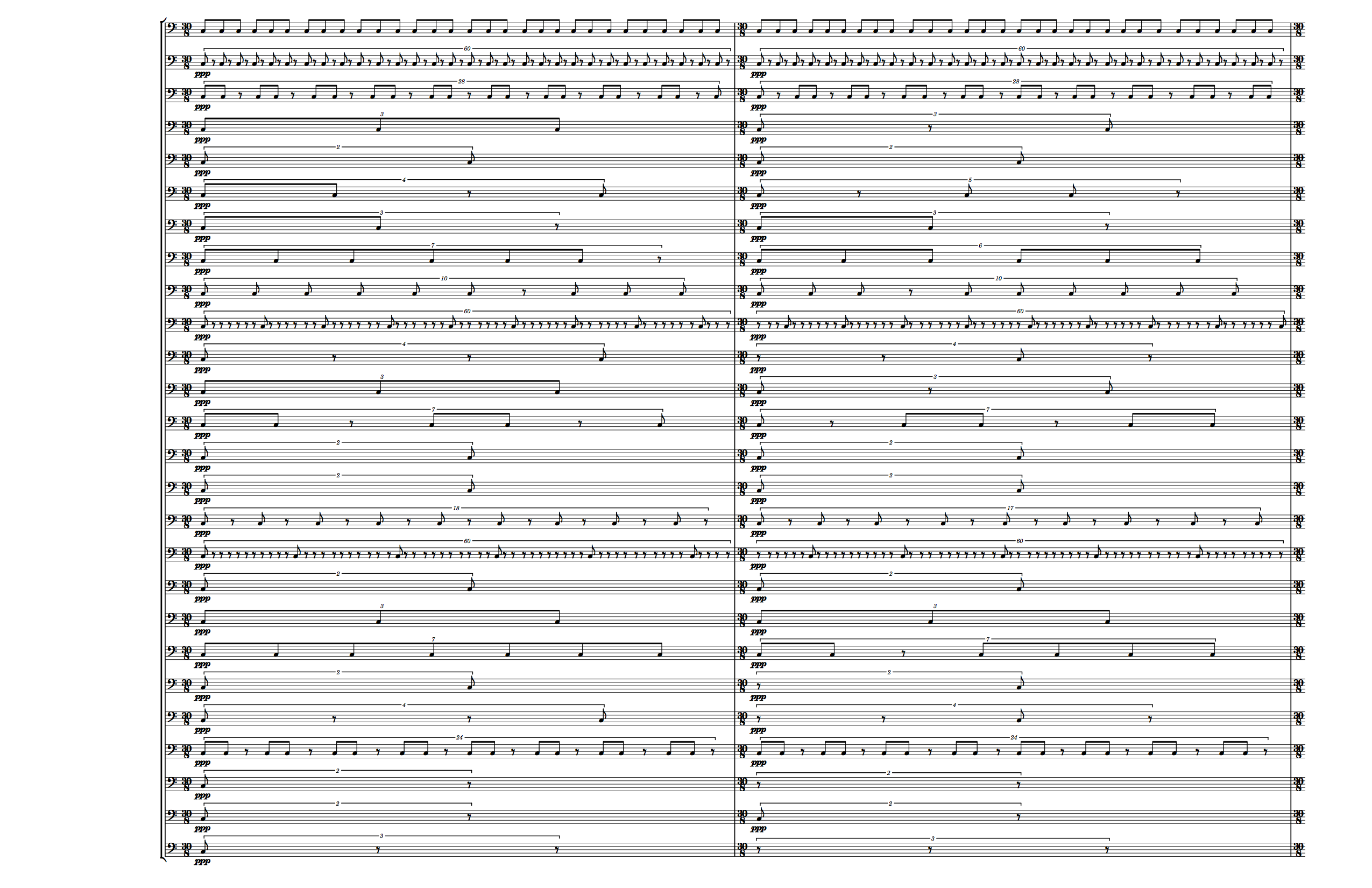

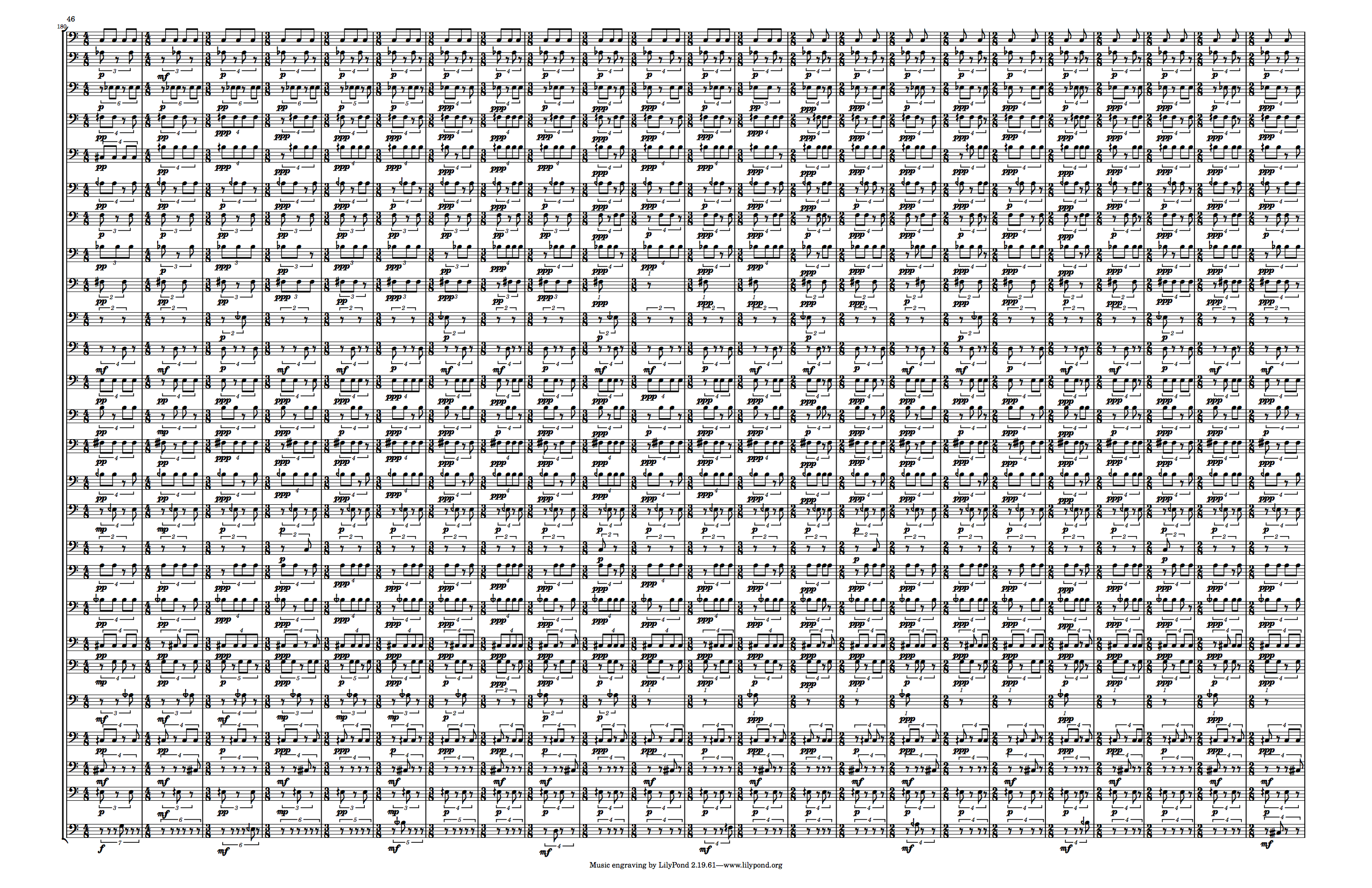

Unsurprisingly, the first page looks the same, since the dynamic level is

universally pianississimo and the pitches don’t start changing until measure 4

About halfway through, we see that both the dynamic and pitch ranges have expanded.

In measure 31 (last measure on the page), we can see the line for V (fifth from the bottom)

change from c to d

And here at the end, we see the full pitch spread, as well as the Z part iterating through the full pitch set.

This is coming together pretty nicely! There’s one more piece, and that’s deciding on how the voices are going to articulate their phonemes. For example:

- for consonants, only the stopped phoneme, or should I add a vowel sound

- if I add vowels, are they the same throughout, or do they change? and, if so, how?

- do the voices hold their notes, or are they all performed as short pulses

I’ll be honest: I’m not really sure of the answers to these questions yet, but if you come back for the next post, I’ll do my best!

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, and want to know when the next one is coming out, follow me on Twitter (link below)!