Alphabet Project, Part 3

Previous entries in this series:

Step 3 - generate polyrhythms

So now that we have a our coordinate sets in JSON, we can start trying to shape them into music.

My original idea was that one letter would serve as a pulse, providing a steady beat, while the rest of the letter parts would modulate their rhythm around that letter, so I decided to start down that road and see where it took me.

For music notation, I love LilyPond. LilyPond, like TeX, is a typesetting system that

that lets you write your music in a plain text file and output it to high quality graphic files. It’s especially

ideal for this project because it’s trivial to generate LilyPond code in Elixir and write it to a .ly file.

So with our tools picked out, let’s go.

V1

The simplest form of this idea is to create a musical measure for each point on the graph’s X axis, and for each letter part

take the letter’s graph’s Y value. The time signature of the measure will have a beat count equal to the Y value for the pulse letter,

and every other part will be a tuplet of letter_Y beats in the space of pulse_Y beats.

The Elixir code for this is similarly simple

defmodule PolyrhythmGenerator.V1 do

...

def pulse_part(letter) do

# `ordered_coordinates/1` parses the JSON file and sorts it by X value

str = ordered_coordinates(letter)

|> Enum.map(fn {_, c} ->

# for the pulse part we want each note to have the same length, so

# we create a measure with a time signature of number_of_beats 8th notes,

# and fill it

"\\time #{c}/8 \\repeat unfold #{c} { c8 }"

end) |> Enum.join("\n")

# write the generated string to a file named `#{letter}.ly`

write_lilypond_file(letter, str)

end

def letter_part(letter, pulse) do

# load the pulse values so we can calculate the denominator

# value for the tuplet

pulse_coords = ordered_coordinates(pulse)

str = ordered_coordinates(letter)

|> Enum.map(fn {i, c} ->

pulse_count = pulse_coords[i]

# we don't need to re-state the time signature since LilyPond

# only requires it to be set in one part, so all we need to do

# is generate and fill a tuplet proportionally fitting this part's

# number of 8th notes into the measure

"\\tuplet #{c}/#{pulse_count} { \\repeat unfold #{c} { c8 } }"

end) |> Enum.join("\n")

write_lilypond_file(letter, str)

end

...

endSome visual examples might be in order. Using a as the pulse letter, the generated LilyPond code looks like

a.ly

aMusic = {

\clef "bass"

%% `\time x/y` sets a time signature with `x` beats and a `y` subdivision

%% `\repeat unfold x { music }` repeats `music` `x` times, writing it out

%% in full to the score, instead of using `|: :|` repeat bar lines

%% "c" is C3, the C below middle C,

%% so we set bass clef above to avoid ledger lines

\time 30/8 \repeat unfold 30 { c8 }

\time 30/8 \repeat unfold 30 { c8 }

\time 30/8 \repeat unfold 30 { c8 }

\time 30/8 \repeat unfold 30 { c8 }

...

196 other measures

...

\time 2/8 \repeat unfold 2 { c8 }

\time 2/8 \repeat unfold 2 { c8 }

}b.ly

bMusic = {

\clef "bass"

\time 30/8 \tuplet 48/30 { \repeat unfold 48 { c8 } }

\time 30/8 \tuplet 48/30 { \repeat unfold 48 { c8 } }

\time 30/8 \tuplet 48/30 { \repeat unfold 48 { c8 } }

\time 30/8 \tuplet 48/30 { \repeat unfold 48 { c8 } }

...

196 other measures

...

\time 2/8 \tuplet 3/2 { \repeat unfold 3 { c8 } }

\time 2/8 \tuplet 3/2 { \repeat unfold 3 { c8 } }

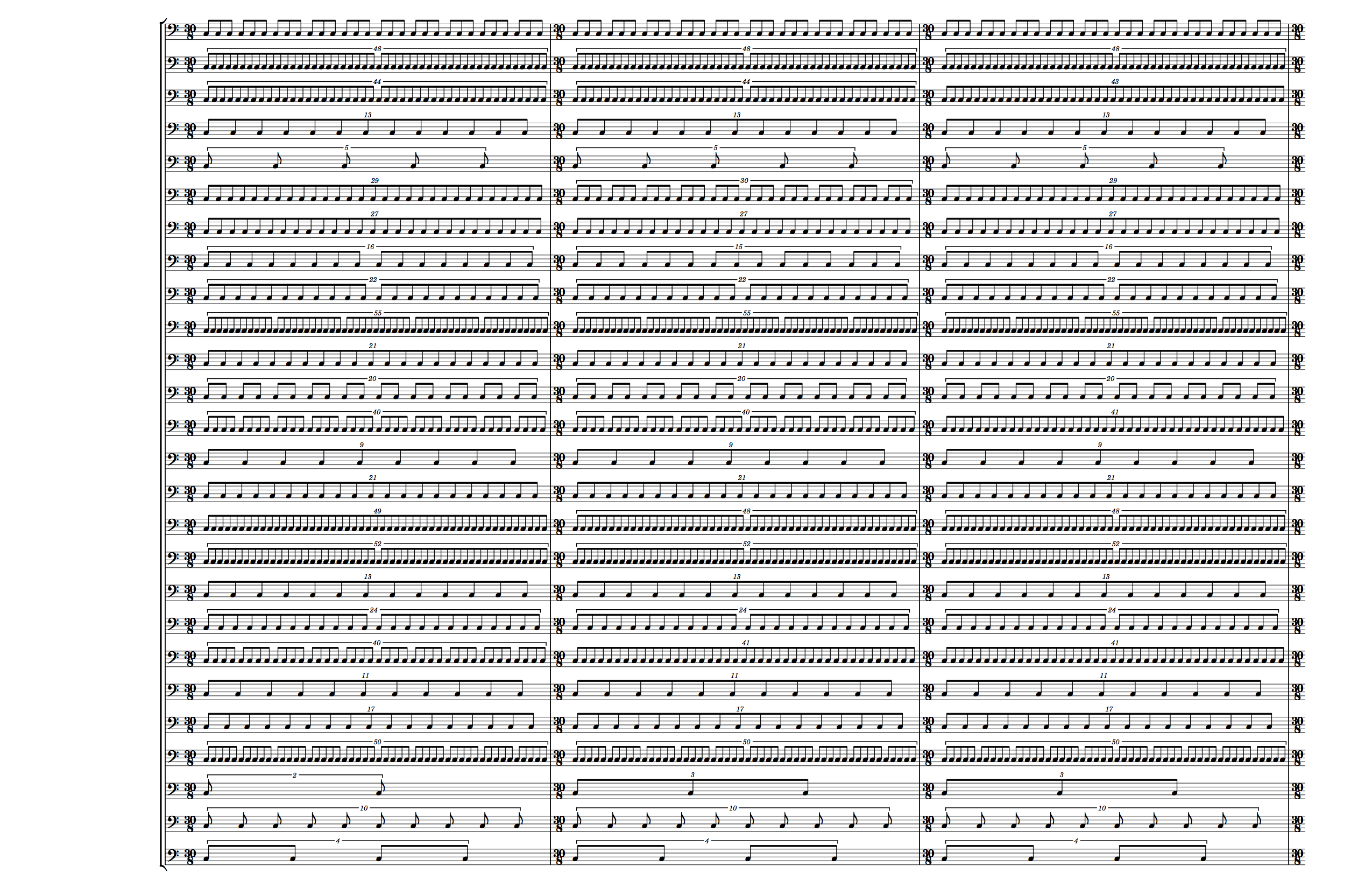

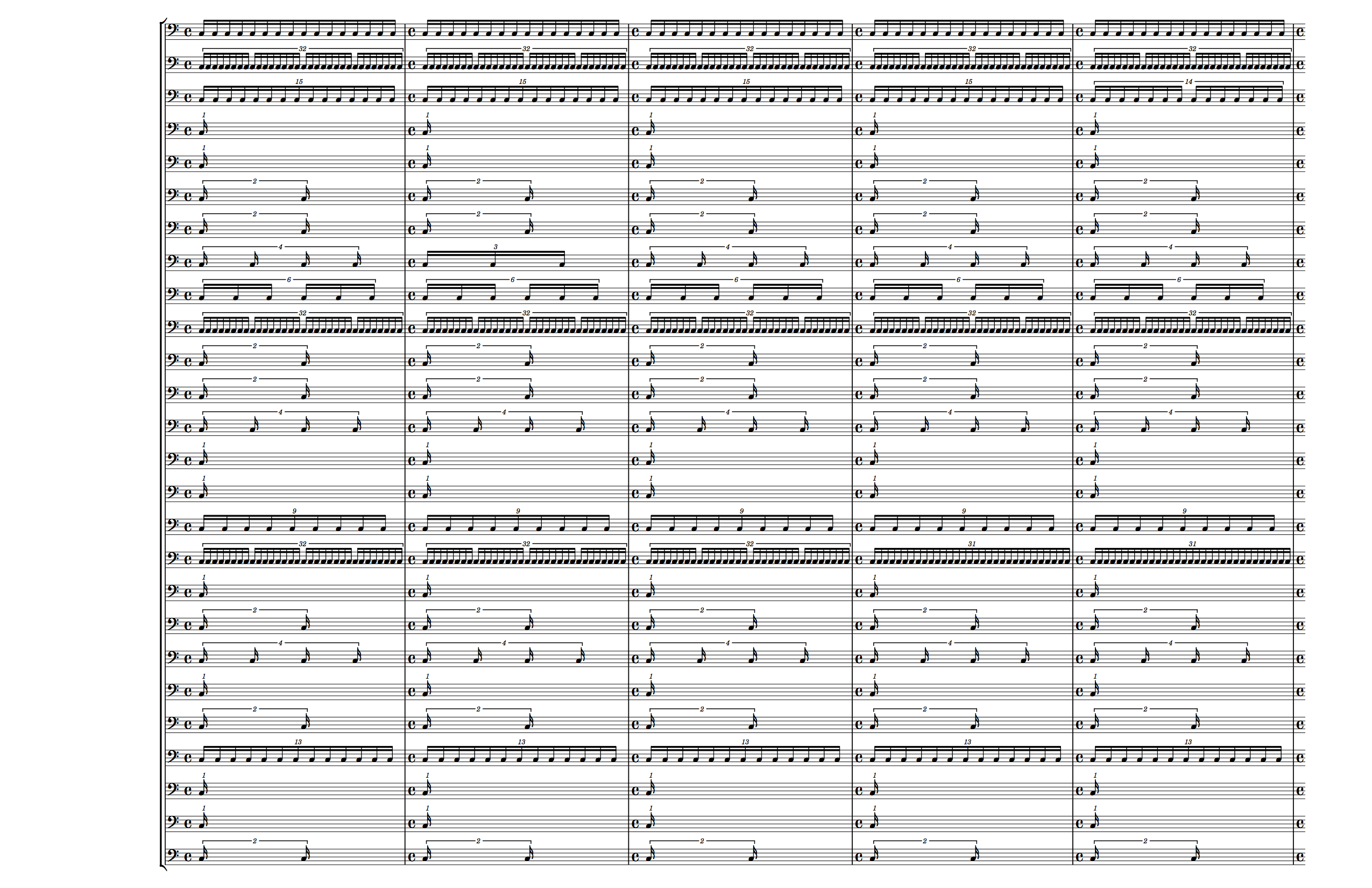

}Compiling all of this to a score, we see the first page (click on the score to zoom in):

Ok, this isn’t too bad, given the idea. The shifting polyrhythms are definitely there. There are some pretty big tuplets there too, but if the pulse (the top line of the score, these are displayed alphabetically) is reasonable enough, they’re not physically impossible for a singer to produce.

But, if we look at the last page:

Again, our pulse is at the top, and now the biggest tuplet is 2 pulse (“a”) beats to 52 “y” beats (second staff from the bottom). If we want to keep the pulse steady throughout the whole piece, either these last measures are absolutely impossible for any non-electronic instruments to produce, or the opening measures are almost unbearably slow. So I think we need to finesse this approach a bit.

(As an aside: I may well use this formulation to create an electronic/MIDI-based composition, where human physiology isn’t a limiting factor, but for now I’m really interested in this being a human-performable vocal piece, so I’m moving on)

V2

For this version I wanted to try to reduce the range of tuplet ratios in order

to increase the performability of the piece. To that end, I added code that took

the coordinates for a letter’s graph, found the maximum Y value, and divided

each point by that value, resulting in a set of ratios between 0 and 1.0

coordinates = ordered_coordinates(letter)

# Find the highest Y value for the line...

{index, max_y} = Enum.max_by(coordinates, fn {x, y} -> y end)

# and map the Y values by dividing them by that max value

# so that each ratio is between 0 and 1.0

# `reduce/2` returns a ratio as a tuple of {numerator, denominator}

# reduced to the simplest form of the ratio (e.g. {1, 2} instead of {2, 4})

# The ratio is stored as a tuple to avoid compounding floating point errors

Enum.map(coordinates, fn {x, y} -> {x, reduce(y, max_y)} end)I decided for this version, since we’re using the ratios, rather than the raw Y values, to make the pulse a steady, unchanging 16th note pulse.

Each ratio is paired with the pulse’s ratio for that measure, and multiplied by the reciprocal of the pulse’s ratio. Since we want the pulse to be steady, in each measure we can get a ratio of 1:1 by multiplying the ratio by its own reciprocal, and so we apply the same function to the ratios for every other part in the measure to determine the final ratio for the measure.

I decided for this version, since we’re using the ratios, rather than the raw Y values, to make the pulse a steady, unchanging 16th note pulse. Given that, each of the ratios calculated above is multiplied by 16, and then rounded to an integer to generate the numerator for the tuplet.

Below is the full, annotated Elixir code for generating these musical parts:

defmodule PolyrhythmGenerator.V2 do

...

def pulse_part(letter) do

music = ordered_coordinates(letter)

|> Enum.map(fn _ ->

# every measure is 4/4, with the pulse as steady 16th notes

"\\time 4/4 c16[ c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c]"

end) |> Enum.join("\n")

write_lilypond_file(letter, music)

end

def letter_part(letter, pulse) do

# Generate the tuplet numerators (see below)...

music = part_ratios(letter, pulse)

|> Enum.map(fn n ->

# and generate the lilypond string for the tuplet

"\\tuplet #{n}/16 \\repeat unfold #{n} { c16 }"

end) |> Enum.join("\n")

write_lilypond_file(letter, music)

end

def pulse_ratios(letter) do

coordinates = ordered_coordinates(letter)

# Find the highest Y value for the pulse line...

{index, max_y} = Enum.max_by(coordinates, fn {x, y} -> y end)

# and map the pulse Y values by dividing them by that max value

# so that each ratio is between 0 and 1.0

# `reduce/2` returns a ratio as a tuple of {numerator, denominator}

# reduced to the simplest form of the ratio (e.g. {1, 2} instead of {2, 4})

# to avoid compounding floating point errors

Enum.map(coordinates, fn {x, y} -> {x, reduce(y, max_y)} end)

end

def part_ratios(letter, pulse) do

# load up the pulse ratios

pulse = pulse_ratios(pulse) |> Enum.into(pulse, %{})

coordinates = ordered_coordinates(letter)

{index, max_y} = Enum.max_by(coordinates, fn {x, y} -> y end)

# Find the ratios for the current letter line, also a set of

# {numerator, denominator} ratios

coords = Enum.into(Enum.map(coordinates, fn {x, y} -> {x, reduce(y, max_y)} end), %{})

# iterate through the X-axis indices

Enum.sort(Map.keys(coords))

|> Enum.map(fn i ->

# decompose the pulse ratio for measure `i`

{pn, pd} = pulse[i]

# decompose the current letter's ratio for measure `i`

{n, d} = coords[i]

# create the ratio of multipling the letter's ratio by the reciprocal

# of the pulse's ratio. We do this because the multiplying the pulse

# ratio by its reciprocal equals 1, which works out since we want it

# to be the steady pulse.

reduce(n * pd, d * pn)

# Then multiply the resulting ratio by 16 (the number of pulses in a measure)

# and round it off to an integer to determine the tuplet numerator

end) |> Enum.map(fn {x, y} -> round(16 * x / y) end) #|> Enum.min

end

...

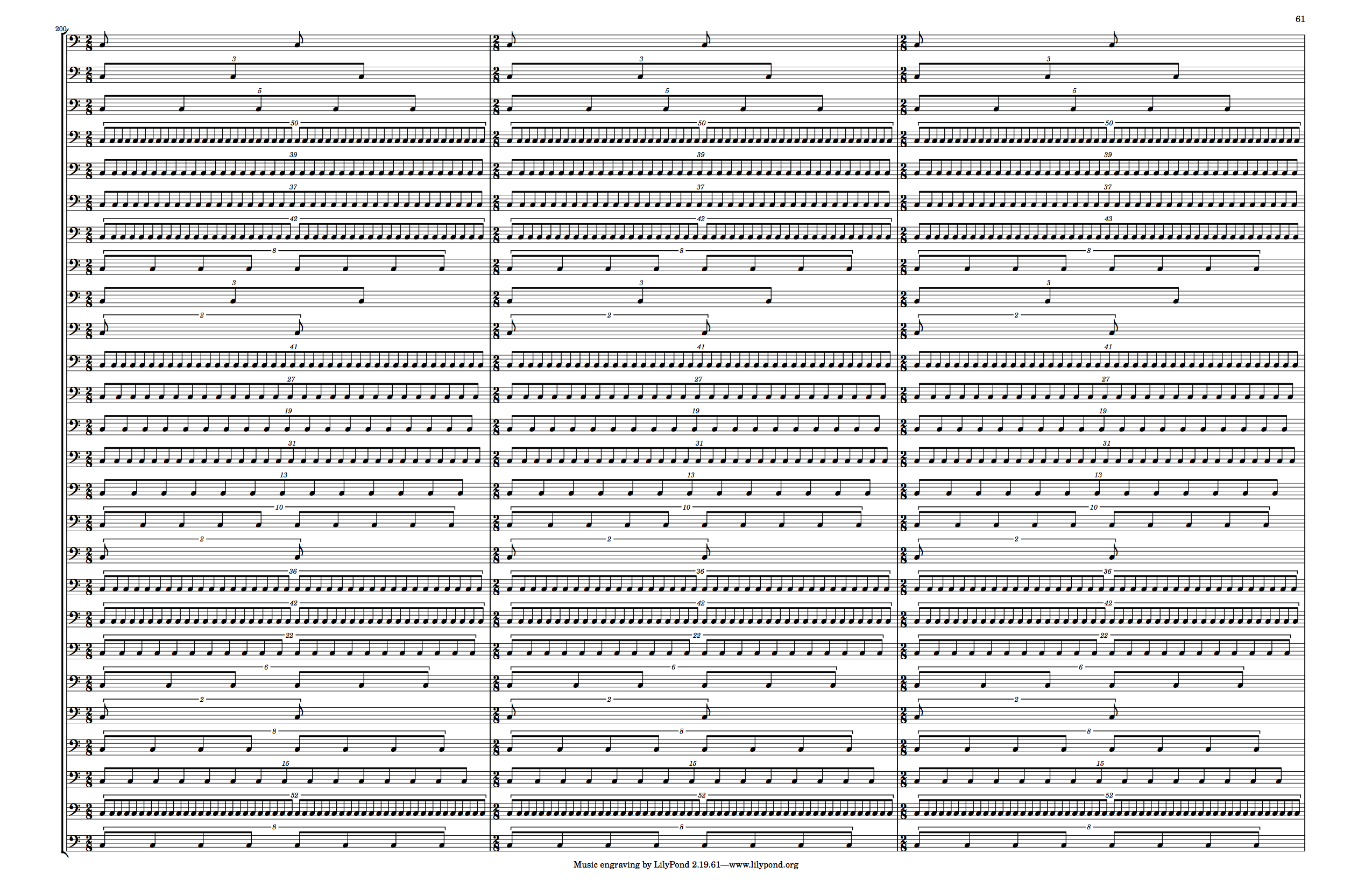

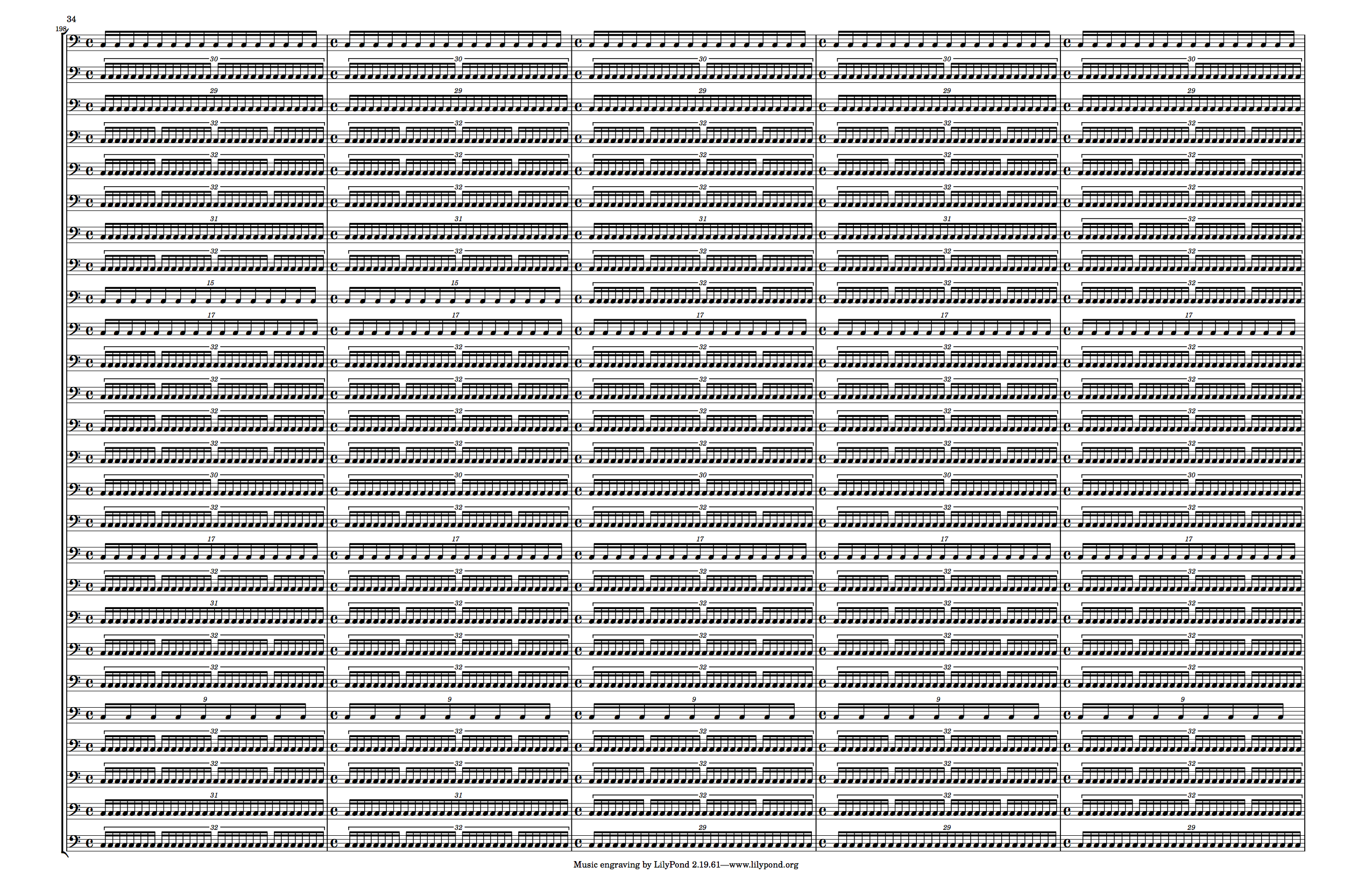

endAnd the first page:

Ok! That looks reasonable. But we ran into trouble by the last page, so let’s take a look at that too and see if we did any better?

Ok, no, that’s even worse. If you open the full size image, you can see we have many ratios of 200+:16, so that a single measure won’t even fit on the page. So clearly there’s more work to be done on reining in these ratios.

V3

Ok, so the problem is that the ratios just have way too big a range between their minimum and maximum. In order for this piece to be human-performable, that range needs to come down. What I want to be able to do is maintain the relative differences between the ratios, but just constrain the minimum and maximum values.

Fortunately, Processing has the function map(), which takes a value, a range currently containing that value, and a range into which to map the original value.

// map(value, currentRangeMin, currentRangeMax, targetRangeMin, targetRangeMax);

map(5, 0, 10, 0, 1); //=> 0.5Even more fortunately, a quick search through the Processing source code shows that the implementation is, error handling aside, one line of arithmetic, and thus easily copyable over to Elixir:

def map_to_range(v, start_c, stop_c, start_t, stop_t) do

start_t + (stop_t - start_t) * ((v - start_c) / (stop_c - start_c))

endThis means there’s really one only step we need to add to the previous implementation, and that is to take the ratios for a graph, find the min and max ratios, and map the whole range to a performable range of tuplets. Since our pulse is 16th notes, I decided the lowest ratio should be 1/16, or one note per measure, and I set the highest ratio to be 2, which is fast to articulate, but definitely possible.

This is a simple change to code

def part_ratios(letter, pulse) do

pulse = pulse_ratios(pulse)

coordinates = ordered_coordinates(letter)

{index, max_y} = Enum.max_by(coordinates, fn {x, y} -> y end)

pulse = Enum.into(pulse, %{})

coords = Enum.into(Enum.map(coordinates, fn {x, y} -> {x, reduce(y, max_y)} end), %{})

ratios = Enum.sort(Map.keys(coords))

|> Enum.map(fn i ->

{pn, pd} = pulse[i]

{n, d} = coords[i]

# multiply the fraction by the reciprocal of the pulse ratio so that the pulse always == 1

reduce(n * pd, d * pn)

end) |> Enum.map(fn {x, y} -> x / y end)

# NEW: find the min and max ratios for the part and map every ratio

# from that range to 1/16 - 2

letter_max = Enum.max(ratios)

letter_min = Enum.min(ratios)

ratios = Enum.map(ratios, &__MODULE__.map(&1, letter_min, letter_max, 1/16, 2))

Enum.map(ratios, fn x -> round(x * 16) end)

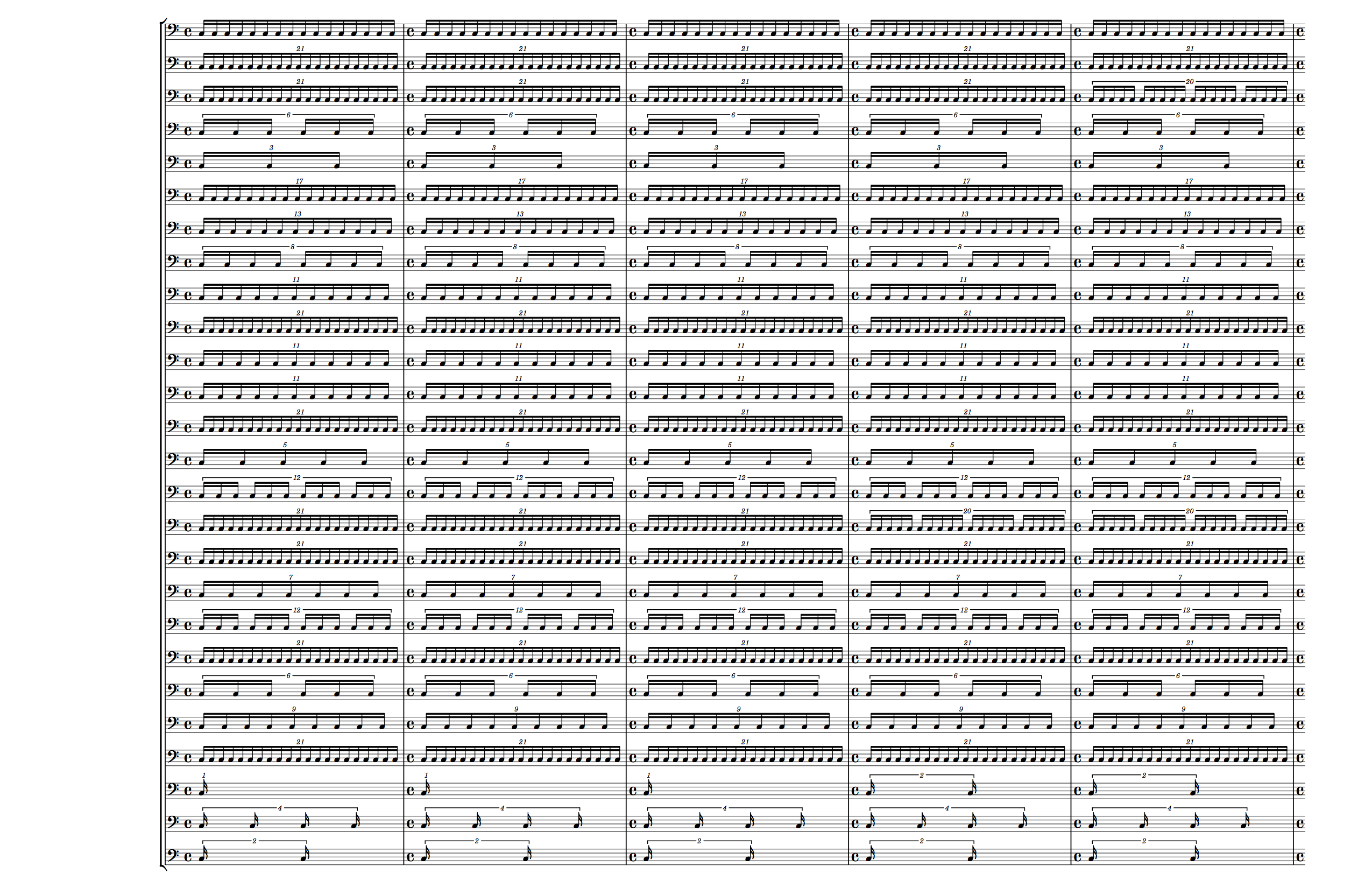

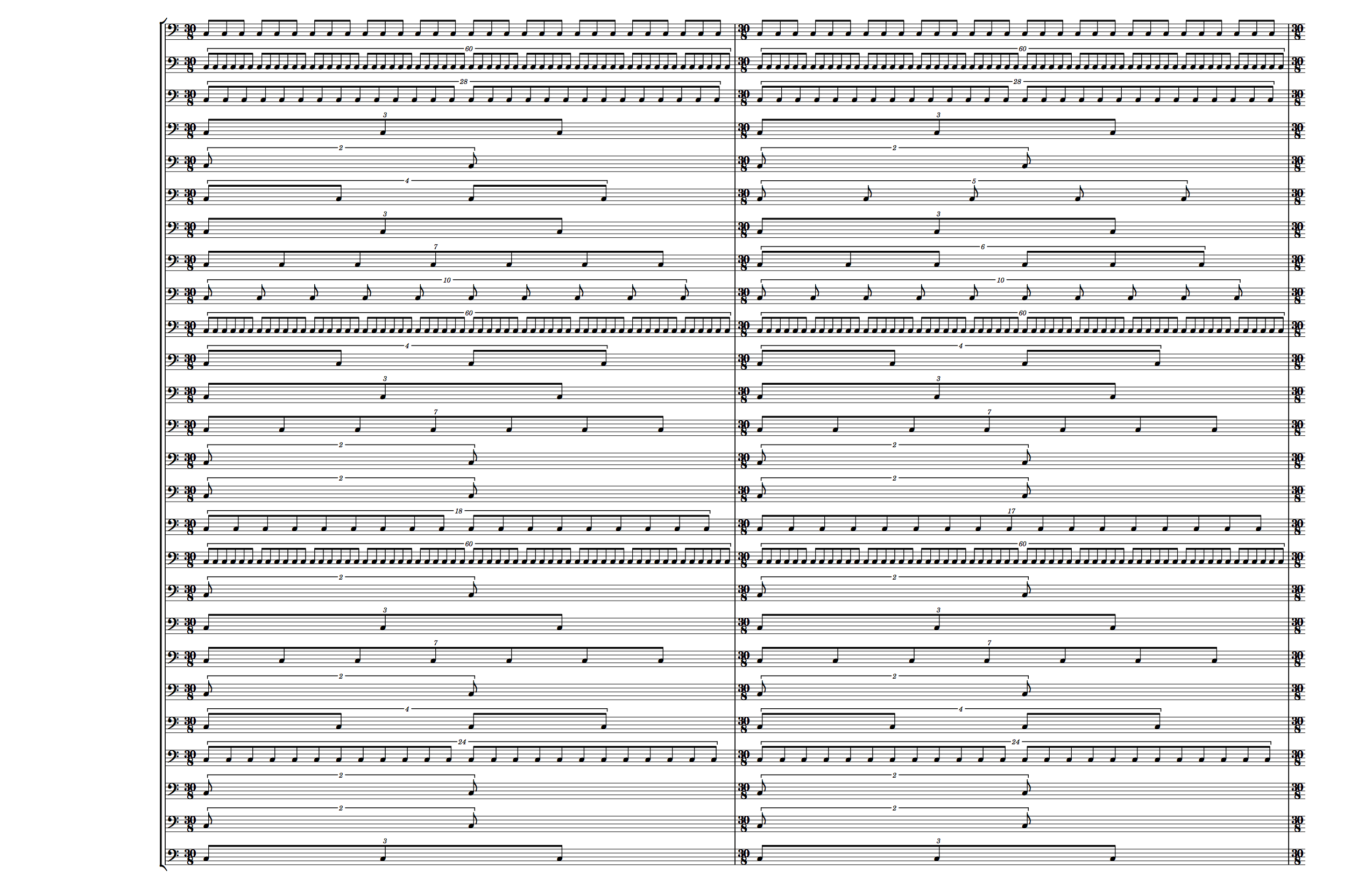

endAnd the resulting first and last pages:

Well hey, doesn’t that look (theoretically) singable by humans! This could work, but now that we’ve got the ratios working, I want to try one more variation.

Looking at the score above, every part articulates on the downbeat of each measure, which would create a macro pulse throughout the entire piece.

What if we combine the calculated rations from V3 with the structure from V1 and V2, where the length of each measure is the absolute Y value for the pulse?

defmodule PolyrhythmGenerator.V4 do

...

# The code is identical except for `pulse_part/1` and `letter_part/2`

def pulse_part(letter) do

str = ordered_coordinates(letter)

|> Enum.map(fn {_, c} ->

# The time signature is based on the pulse letter's Y value

"\\time #{c}/8 \\repeat unfold #{c} { c8 }"

end) |> Enum.join("\n")

write_lilypond_file(letter, str)

end

def letter_part(letter, pulse) do

pulse_coords = ordered_coordinates(pulse) |> Enum.into(%{})

music = part_ratios(letter, pulse)

|> Enum.map(fn {i, r} ->

# Find the matching pulse count for the current measure

pulse_count = pulse_coords[i]

# The numerator for the tuplet is `measure ratio` * `pulse count`

c = round(r * pulse_count)

"\\tuplet #{c}/#{pulse_count} { \\repeat unfold #{c} { c8 } }"

end) |> Enum.join("\n")

write_lilypond_file(letter, music)

end

...

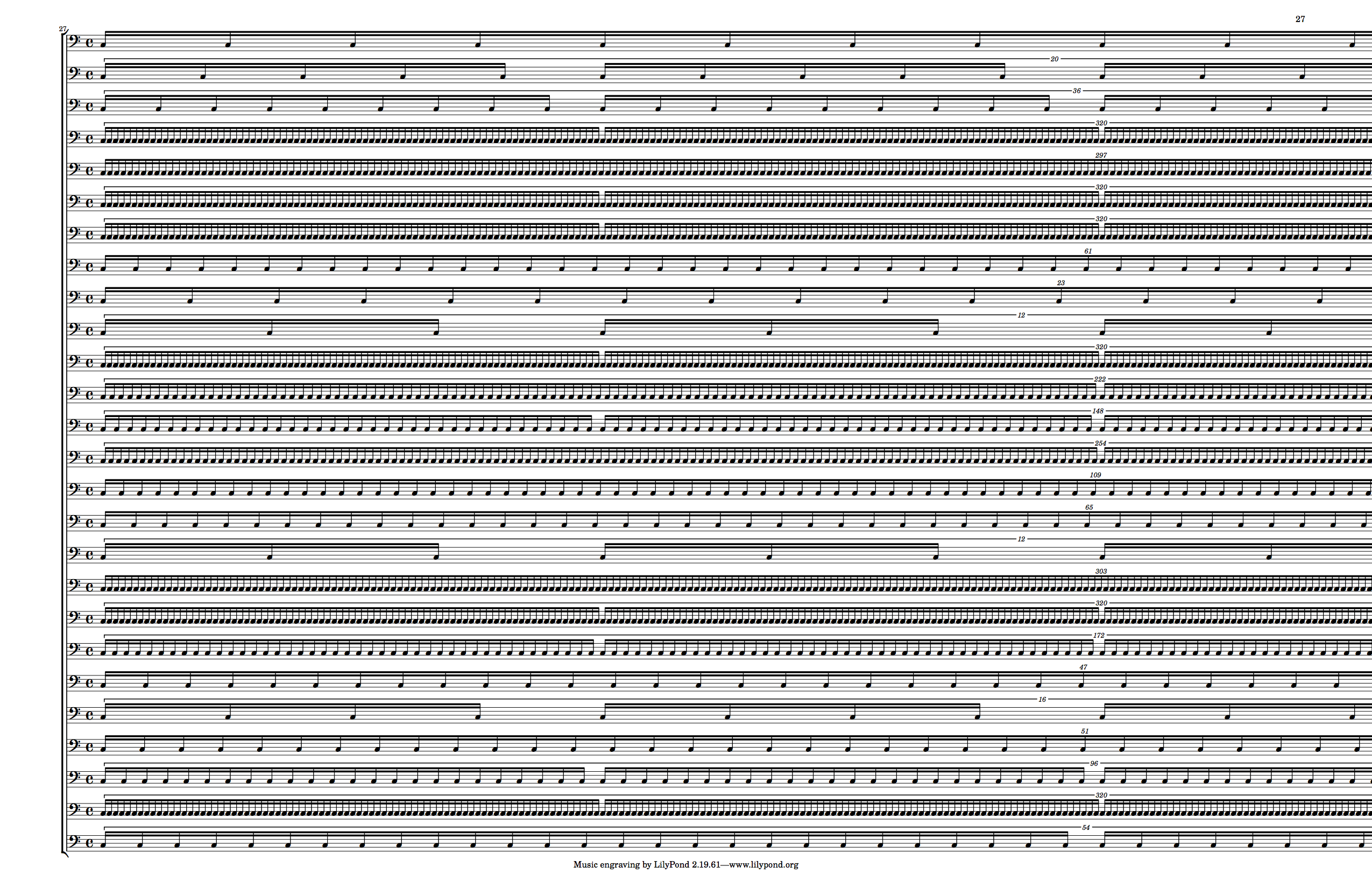

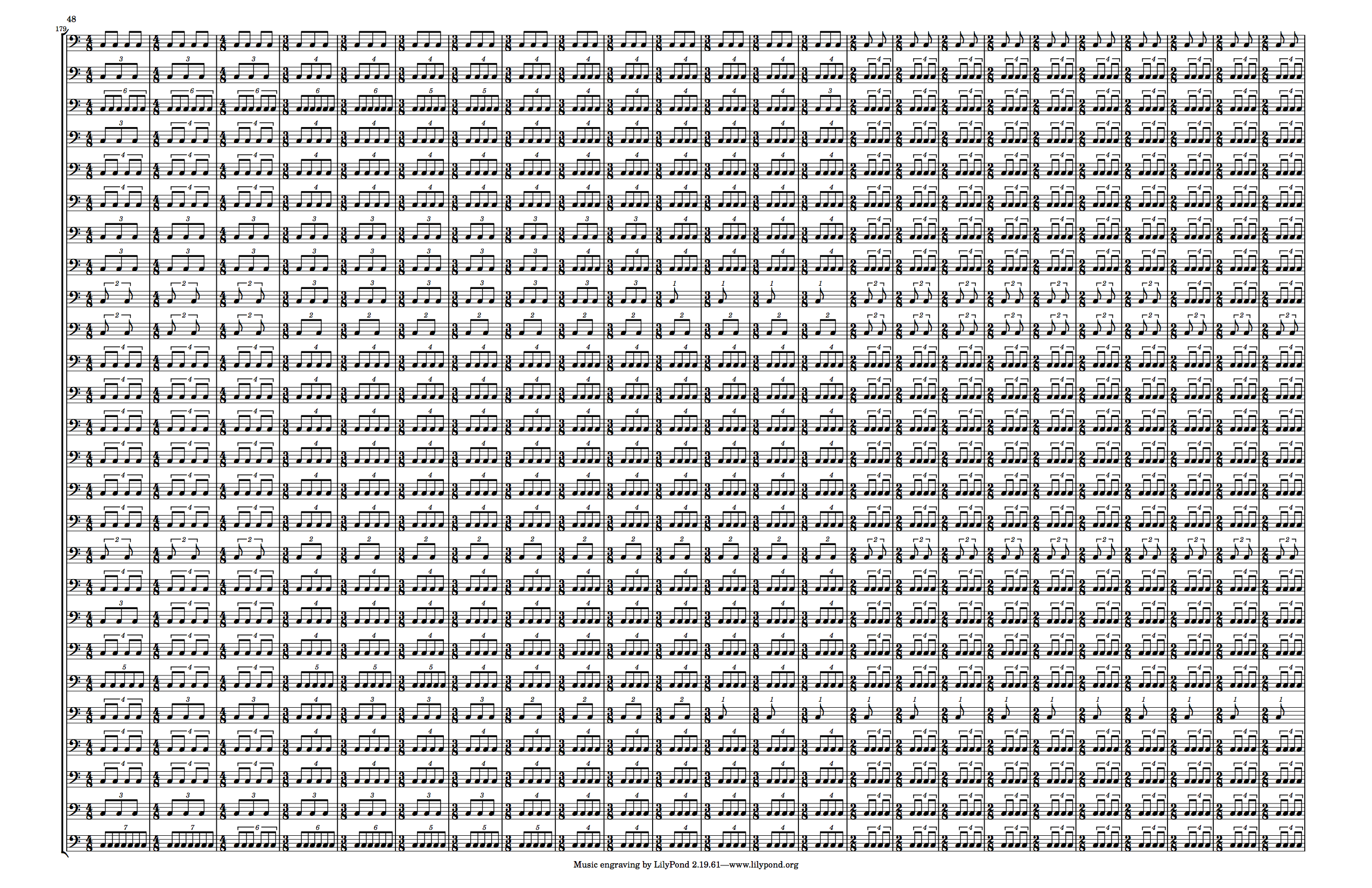

endAnd the output:

While this version begins with a similarly open set of ratios, the ending is very different, much more intense as the measures get shorter and the downbeats closer together.

At this point we’re down to aesthetics when it comes to whether to move forward with V3 or V4. For now, I’m going to go with V4, since I like the variation in measure length.

Now that we’ve got a basic rhythmic document laid out, the next steps are to turn it into something a bit more compelling musically. Stay tuned!

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, and want to know when the next one is coming out, follow me on Twitter (link below)!